Colonial and anticolonial sentiments lead Dutch scholars to ignore and marginalise Indies postcolonial history

Lizzy van Leeuwen

|

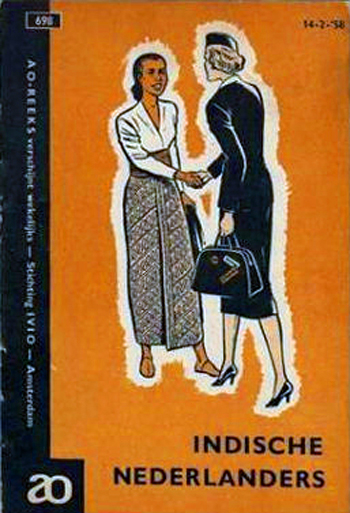

Modernity meets tradition in a Dutch manual on how to deal with‘Oriental’ migrants, published in 1958Lizzy van Leeuwen |

In December 2009, several prominent Dutch scholars petitioned their government to formally acknowledge the birth of the Indonesian Republic as occurring in 1945, slating the government for continuing to represent 1949 as the year of the nation’s inception in NRC Handelsblad, a leading Dutch newspaper. The question of the proper date of birth of independence of the former colony has been a bone of contention in the Netherlands for decades. Indonesians declared their independence unilaterally two days after the Japanese capitulation that ended the Second World War, on 17 August 1945; after four years of violent struggle the Dutch transfer of sovereignty finally followed on 27 December 1949.

As well as burdening the ‘new’ bilateral relationship between former colony and coloniser, this clash of national calendars soon proved to be a major obstacle within the Netherlands. The Dutch-Indies decolonisation process was accompanied by a diversity of stories of repatriation; conscripts, white settlers, the mixed-descent population (Indos) and Moluccan colonial soldiers all have painful memories of survival and taking leave. These are all stories of entitlement that revolve around and clash with the two contested dates of Indonesian self-determination.

Not surprisingly, coming to terms with the bitter experience of violence, captivity and expulsion proved to be burdensome for many postcolonial migrants. At same time, feelings of frustration and trauma have been exacerbated by the fact that a postcolonial debate continues to be evaded in the Netherlands.

Recognition or neglect?

Recently, the Dutch government finally tackled the controversy about the ‘correct’ date of Indonesian independence. In August 2005 the Dutch Minister of Foreign Affairs, Ben Bot, joined the celebration of the sixtieth birthday of Indonesian independence in Jakarta, thereby ending the 60-year old stand-off. He also officially declared that ‘the Dutch Cabinet and people liberally accept that Indonesian independence, politically and morally, commenced in fact in 1945’. Indonesia accepted Minister Bot’s statement.

As Bot and his Indonesian hosts realised, this statement was of possibly more significance in the Netherlands than for the bilateral relationship, putting an end to the polarising effects of the controversy in Dutch postcolonial communities. A complicated postcolonial hurdle appeared to have been solved and all Dutch protagonists involved – politicians, Indies migrants, even the Indies war veterans – seemed relieved by this unexpected closure.

But the petition in NRC Handelsblad four years later made clear that the Netherlands’ postcolonial problems are not that easily solved. The signatories advocated a re-writing of this last colonial chapter in a way that integrates the ‘official story’ with the ‘other story’. They proposed merging the Dutch refusal to acknowledge the republic in 1945 with the violent episodes of 1945 to 1949, stating that to ‘accept’ independence is not the same as to ‘acknowledge’ it.

The explicit recognition of historical and political facts is a matter of ‘acceptance’ as well as ‘acknowledgment’. International law recognises the 1949 transfer of sovereignty and Bot had no intention of changing that. He just made a political gesture; everybody knew this was all he could do. The true significance of the petition lies in its domestic postcolonial meaning. It appears to be a case of ritualised Dutch colonial guilt-and-remorse expressed by seasoned professors, but a closer look reveals that more is at stake

.A remarkable passage in the petition addresses the elderly postcolonial migrants: ‘Many Dutch, specifically from the older generations who still maintain close ties with Indonesia, are driven to resolve the sixty years of neglect. If this doesn’t happen during their lifetime, the issue will be a lost case and younger generations will later falsely regard the issue as resolved.’ This is a dubious suggestion because the people at stake, the elderly Indies-Dutch (especially the Indos), are generally shocked when the date of 17 August 1945 is mentioned. In their experience, this day did not so much herald Indonesian independence as set in motion the terror of the Bersiap period (1945-46) at the start of the war for independence. In this chaotic period, the lives of thousands of their relatives were lost.

Even more dubious is the fact that the way the passage is phrased – in particular the word ‘neglect’ – could as well relate to the postcolonial scandal of the so-called back-pay affair, when the Dutch government persistently refused to pay the overdue salaries of those who were prisoners of war during the Japanese occupation. This injustice has led to enduring frustration and anger among Indies postcolonial migrants, who have undertaken political lobbying, class actions and protests in an attempt to find public redress, but to no avail. None of the professors who signed the petition have ever lent credibility to the long-lasting back-pay affair, although it is of much greater social significance in the Dutch postcolonial context than the Dutch-Indonesian relationship. One of these professors recently dismissed the back-pay affair entirely by coining the expression ‘Indo claiming culture’, insinuating that Indos are simply dissatisfied and demanding citizens.

Knowledge monopoly

The narrow focus of the Dutch academic elite regarding postcolonial affairs has a long history. The treasures of knowledge regarding the East Indies have always been close to the heart of the Dutch nation. There is an intimate relationship between knowledge and power, for the ultimate possession of the Indies colony was not accomplished by the merchants or by officials, but by scientists.

Knowledge – linguistic, ethnographical, agrarian or geological – was the key to colonial exploitation. This explains why academics were close to successive colonial governments, often occupying prestigious positions within them. In the first centuries of colonial domination academics necessarily relied on local knowledge. However, after a while local knowledge became threatening because it proved difficult to bring under total control. Local knowledge escaped Dutch scientific standards as it covered the religious as well as the supernatural. Here lies the root of the discrimination against Indos, for they used to be ‘fluent’ in two conflicting knowledge systems, making them liable to accusations of being latent traitors and defectors.

Still, the production of countless statistics, reports and tabulations meant that Western knowledge acquired at least the semblance of total control. The colonial project – obsessed by numbers – took on the shape of one great scientific-quantitative enterprise. After 1900, the idea of a ‘civilising mission’ gave new impetus to the colonial project. In the ensuing modernisation process, rationality and efficiency became household terms. Key positions in colonial administration, trade and industry went automatically to Dutch expatriates, who kept themselves apart from the local society. The freshly-arrived in ‘Tropical Holland’ held on to their European gaze in order to avert the process of ‘becoming Indies’, a concept associated with slackening, moral degeneration and eventually ‘losing touch with Holland’. The new field of Indology, an exclusive feature of Dutch universities, supplied the training for this gaze. It delivered experts who never had set foot in the tropics.

|

The author in animated discussion with elderly Dutch Indos at the Pasar Malam Fair in The HagueLizzy van Leeuwen |

The hierarchy of knowledge of the East Indies was part of a well-planned strategy to uphold colonial law and order. All knowledge gathered by Indologists shipped to Leiden and integrated in the archives of the Royal Institute of Linguistics and Ethnology in Leiden (KITLV), which still houses the world’s biggest Indonesiana collection. The enduring academic monopoly on colonial knowledge finally led to a situation of undisputed hegemony. The transfer of sovereignty in 1949 did not remove the Dutch scientific grasp on Indonesia. ‘Indonesianists’ – the successors of the Indologists – still academically possessed the Indies as they used to do. There was just one adaptation: the colonial project was swapped for an anticolonial stance. Basically, this was a matter of switching labels. The ‘civilising mission’ was renamed the ‘bilateral development relationship’.

Postcolonial marginalisation

In Holland, the colonial monopoly on Indies knowledge was maintained by carefully separating survivor discourse (the stories of war and deprivation) from expert discourse. All ‘coloured’ knowledge, brought to Holland by Indies postcolonial migrants, was deemed incompatible with the white academic knowledge of Indonesia. Moreover, against the background of the new, worldwide sentiment of anticolonialism, the postcolonial migrants were suspected of being ‘dirty colonials’ possessed by vengeful sentiment. This point of view led to complete neglect of the Indies postcolonial migrant group as a subject of academic interest. Only the government regularly ordered reports on their assimilation process. By the early 1960s, the painful decolonisation episode seemed at a distance and the Indies migrants appeared to be successfully integrated into Dutch society. But a series of developments in the second half of the 1960s spoiled matters and changed the postcolonial scene significantly.

In 1962, the Netherlands had to abandon its last outpost in the former Indies, New Guinea. In the following years, the general postcolonial mood changed. Firstly, a revival of historical interest in World War II, especially the fate of the Jewish population, drew attention away from postcolonial issues. Then, new sentiments about colonialism began to develop, influenced by the worldwide radical revolt in universities and locally by Suharto’s seizure of power in Jakarta.

A sudden rush of panic engulfed Holland after a TV-program was broadcast that mentioned Dutch war crimes in Indonesia. This had immediate effects. The general indignation about American imperialism in Vietnam changed overnight into an immense but partly suppressed embarrassment about Dutch imperialism in Southeast Asia. This sense of embarrassment again brought Indies migrants – and not just the war veterans – into a negative light. Their presence was a constant reminder of the painful past.

The 1970s left-wing politicisation of universities affected virtually all Dutch academic institutions. Academic-radical coteries took over institutional power and criticised the Dutch (and global) political and social status quo for years to come. Among them were the new generation of Indonesianists, who felt inspired either by Wertheim or by familial-colonial ties. Leftist themes were easy to come by. In Indonesia, repression and injustice abounded, as did the trauma of colonial guilt in Holland. As a consequence, no research space could be spared for the difficult questions regarding postcolonial issues. There was a tendency to lay claim to ‘the Indies’ and ‘Indonesia’ as exclusive ‘moral’ and academic provinces. The unrelenting condemnation of Suharto’s repressive politics seemed to relate, in an obscure but comfortable way, to the redemption of colonial guilt.

There was still no scholarly interest in the history and experience of the Indies postcolonial migrants. In 1986, a few members of the Indies-Dutch community founded an Indies Scientific Institute in The Hague, which, helped by state subsidies, undertook the neglected documentation and historiography of the colonial experience of Indos, but did not publish any major studies on Indies history or culture. Academic research programs focusing on (post)colonial Indies history have started only recently, at the insistence of Indies communities. But the studies that have since been published, including my book, Ons Indisch Erfgoed (Our Indies Heritage), have been met with an ominous silence in academia.

Need for debate

The absence of a critical public debate about postcolonial issues in Holland can be attributed to scholars who continue to claim the field of the ‘Indies’ and ‘Indonesia’ as their own. Their research agendas have never included inquiries into the Bersiap period or the murders at this time. They have not considered the price paid for the so-called ‘quiet integration’ of postcolonial migrants. The question of how postcolonial power structures influenced postwar Dutch politics – especially the formation of right-wing politics – has not yet been grappled with. Their research agendas also fail to consider the postcolonial culture of the ‘pure’ Dutch residents of the Indies or the question why so many Indo migrants could not find a way to stay in Holland after repatriation. Now the first generation of Indies migrants is disappearing and much material has been lost.

However, Indies communities have taken the initiative and a grassroots debate on these issues has begun. This bottom-up engagement is a novel development in the Dutch postcolonial context, made possible thanks to the internet. A clear sign of this is the emergence of American, Canadian and Australian Indo voices, which convey a host of different experiences and reflections. These voices tell, for example, rather carefree about the racial discrimination they once experienced in Holland, a subject that is still considered taboo among the majority of Indos who live in The Netherlands. Although academic interest in their history and experience is almost non-existent, Indos of all generations have passionately commenced the exploration of their complicated communal past. This will undoubtedly lead to a more nuanced take on Dutch colonial history and, hopefully, a serious postcolonial debate will begin at last.

Lizzy van Leeuwen (Lizzyvl@xs4all.nl) is an anthropologist and the author of Ons Indisch Erfgoed (2008), Lost in Mall: An Ethnography of Middle-Class Jakarta (2011) and Airconditioned Lifestyles (1997).

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar